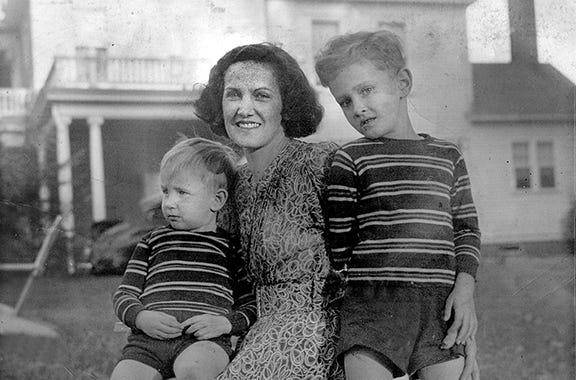

My Mother Taught Me the Dictionary One Word At a Time

Over the two years from the day my brother Pat started school and I got old enough, DeLora Woodring Holland taught me the dictionary from Aardvark to Zymurgy, two hours a day, one word at a time.

Among the effects of the Great Depression for William Harrison Woodring and Ada Fosse Woodring, immigrants from Alsace-Lorraine in the early days of the 20th Century, was the need to have their daughter Mary DeLora withdraw from school after eight years and work at this and that to help support the family that included three younger brothers. “She was a good student, but …” was the way it was explained to me.

My brother Pat was two years and four months older. He entered St. Columba in Louisville’s West End in 1941 and pretty much the next day as I recall Mom sat me down on the sofa about 10:00, after she had finished the breakfast dishes, and opened our dictionary. She said we were going to read it one word at a time. She pronounced it and if it was too much of a mouthful for me, she supported my required struggle to pronounce it. She directed my vision to the word there on the page and spelled it, then asking me to spell it, as I did by pronouncing the letters one at a time in sequence, “a, a, r, d, v, a, r, k.“ She read the definition and asked me to put it in a sentence. “I wish we had an aardvark, but we would have to have a pretty big cage.”

We spent a couple hours with this every weekday morning until she had afternoon chores to do. At that point, she tickmarked how far we had gone and asked me to go back over what I had learned. We had books in the house and she urged me to read them. She said if I came upon a word that was new to me, I should look it up in the dictionary before reading another word in the book.

I recall it as great fun, never a bother, and I think I recall the day two years later when we got to zymurgy and she sent me off to school at St. Columba. I was there for a week until they said I should be in the Second Grade. At one point during that first year of school we had a full school Spelling Bee and I won it. I ate books. The Hardy Boys series that we went to the library to get. Dad’s supply of mysteries. Histories of famous people. I read everything, even what was printed on the matchbooks around the house.

When I was a Senior in High School we were given the I.Q. test, I for Intelligence and Q for Quotient. All it was to me was responding to unfamiliar packages of thoughts and expressions against the clock, with the scoring based on the accuracy of my answers and the speed of getting to them. My score was 146. Maybe forty years later, when the Internet was a child, the Washington Post offered an online IQ test. I got 146. I don’t know what “intelligence” means, and I don’t think anybody else does either. I know that the IQ score is based on indexing, a scoring system in which 100 is the average. The conventional wisdom is that an IQ score of 160 is where genius begins. I think that’s all baloney.

What I believe is that Mary DeLora Woodring Holland, who never went past the Eighth Grade, turned me into a man who fears nothing that is said or written in the English language. That hasn’t kept me from making a lot of stupid mistakes in my long life, but all those are on me. Happy Mothers Day, Mom, if there’s any truth to the rumor that dead people can hear messages sent by living people. In our case, I hope so. If you’ll excuse me, I’ve got a lot of reading and writing to do.